Freedom Summer 1964

Residing in the hills of Miami University's campus lies a memorial preserving a significant part of history.

The city of Oxford, Ohio is known for it's charm, history, and small-town aesthetic. Miami University was chartered in 1809, and to this day is a huge part of of the city's beauty, along with the brick streets, architecture, covered bridges, and serene nature trails. What most people don't know is that Oxford has a profound— and sometimes overlooked— history rooted in the Civil Rights Movement. Tucked into the grassy hills surrounding the Western Campus at Miami University, there lies a magnificent stone memorial that is dedicated to remembering the events and honoring the people involved in Freedom Summer 1964.

The Freedom Summer Project

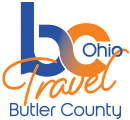

The Civil Rights Movement began a decades-long fight for justice and equality in the United States. In this time, there were numerous activists, demonstrations, and events that led to the signing of the Civil Rights Act on June 2, 1964. In that same month of the same year, a group of organizations, activists, and volunteers continued to fight for equality by tackling the issue of voter intimidation.

Credit : Newspaper graphics, The Civil Rights Bill - Four key provisions and the problems they are designed to correct, ca. 1964. Freedom Summer Text & Photo Archive, Miami University, Western College Memorial Archives, Oxford, Ohio.

The Mississippi Summer Project, which later became known as The Freedom Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign launched with the mission to educate and register Black voters in the state of Mississippi, which was chosen due to its historically low levels of Black voter registration. At the time, this was an extremely dangerous task. Despite much progress of the Civil Rights Movement, southern states like Mississippi still remained segregated, with much violence targeted at Black citizens.

Freedom Summer was organized by civil rights organizations like the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and included nearly 1,000 Black and White volunteers who fought against voter intimidation and discrimination at the polls.

Credit: News Clipping: Lafayette Louisiana Advertiser, June 21, 1964. Freedom Summer Text & Photo Archive, Miami University, Western College Memorial Archives, Oxford, Ohio

The volunteers came from all over the U.S. and were primarily college students and young adults. The main goals of the Freedom Summer Project were not only to increase Black voter registration, but to also gain more media coverage of the issue, and to help educate Black youth in Freedom Schools. This was an important part of the project, as Freedom Schools were organized by the SNCC to help supplement the inferior educational opportunities that were being provided to Black children in the state’s public schools.

Ultimately, the events of Freedom Summer helped convince President Lyndon B. Johnson and congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, the results of Freedom Summer did not come without very real danger and sacrifice.

Volunteers Trained in Oxford, Ohio

Due to the extreme violence and the rise of Ku Klux Klan membership in Mississippi during 1964, The Freedom Summer Project held training sessions intended to fully prepare their volunteers. The organizers needed a secure location to hold their training sessions on how to register Black voters, teach literacy and civics at Freedom Schools, and approach hostile situations with non-violence.

After a different location fell through, the Western College for Women here in Oxford— which is now the Western Campus of Miami University— volunteered to host the training.

Robert P. Moses was one of the major leaders of the SNCC as well as a central figure in the Freedom Summer Project. He helped to recruit and also train hundreds of student volunteers from northern colleges. Many volunteers described him as intense, passionate, soft-spoken, and charismatic.

Credit : Freedom Volunteers in Mississippi. L to R: Robert Moses, Don Winkleman and Roland Duerksen. Freedom Summer Text & Photo Archive, Miami University, Western College Memorial Archives, Oxford, Ohio.

In the month of June 1964 and the month after, groups of volunteers went to training before being sent to Mississippi in different waves. Once there, they would stay with volunteer families while they worked.

The training sessions consisted of speakers, books, and workshops to help educate and mentally prepare volunteers. Robert Moses had pledged his staff and volunteers to “nonviolence in all situations,” which was also taught in the training sessions, along with books like Dr. King’s memoir, Stride Toward Freedom, and Lillian Smith’s novel Killers of the Dream.

One article from the Enquirer in 1964 paints the picture for one wave of volunteers before heading down to Mississippi. This group included 78 students that the article describes as "Carrying guitars, tennis rackets, and textbooks," while boarding two charter buses. The article reads:

"'We're hoping for the best and preparing for the worst,' said Lew Sitzer, Los Angeles, clad in tee shirt and blue jeans...

Tall, blond and mustached, Roy Torkington. Rochester N.Y. said, 'There's a lot of spirit in this group. We've got a job to do, and we're going to do it. It's as simple as that.'"

Credit : Photograph, Two Freedom Summer volunteers teaching children in Freedom School. Freedom Summer Text & Photo Archive, Queens College Special Collections and Archives; Western College.

The volunteers came from all walks of life; from different states, different colleges and different backgrounds, some Black and some White, and some from as far away as Honolulu— they were all united in the form of community and fighting for something they believed in... regardless of the perilous nature of the work that lied ahead.

Much of the training sessions were spent explaining the high-level of scrutiny and violence volunteers would experience while in the South, and teaching them how to respond to those situations with non-violence. Both staff and volunteers were warned about the high probability of being arrested as well. The volunteers continued into the project aware of the risk, but with a firm belief in the mission.

In part of a letter to the Press dated Sunday, July 19, 1964 from Mark and Betty Levy, who were working in a Freedom School in Meridian, Mississippi, they expressed:

"Since we have been in Mississippi the outside world has become quite unreal— in the same way that Mississippi is probably unreal to you. It's hard to describe what it's like to live in a closed society where fear and terror are part of one's daily existence. For us it means being suspect wherever we go: the whites hate our guts; the Negroes accept us only partially— people who they cannot help feeling ambivalent towards. For the Negroes, it means starting each day not knowing whether they will live through the end of it...

Perhaps the most amazing and beautiful thing for us has been to see that even within this sick environment, people can manage to escape with a spiritual freedom that gives them hope greater than we've ever seen before."

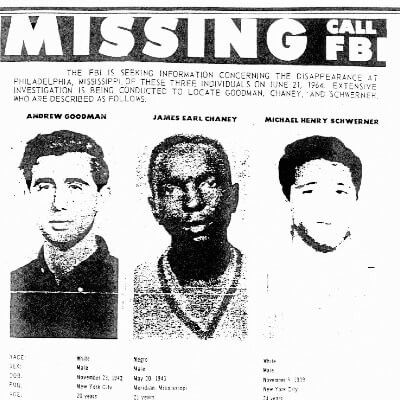

Chaney, Goodman & Schwerner

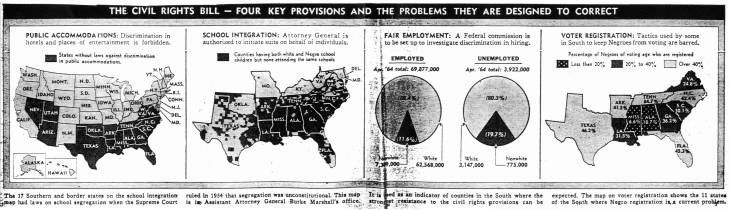

Among the first wave of volunteers that arrived in Mississippi on June 15, 1964 were two White students from New York, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, a local Black man. These three men— two CORE Staff Members and a Freedom Summer volunteer— were all said to be passionate activists who truly believed in the work they were doing, and hoped to make a difference in society.

On June 21, 1964 the three activists left Meridian, Mississippi in a blue station wagon to investigate a church burning in Neshoba County, because it had been a planned site for a Freedom School. On the drive back, their station wagon, known to law enforcement as a CORE vehicle, was stopped, and police arrested all three. Back in Meridian, CORE staff began calling nearby jails and police stations, inquiring about the three men— their standard procedure for when organizers failed to return on time.

There were no records of the calls according to the jail in Philadelphia, Mississippi where Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman were kept until 4pm that day. The three men were reported missing as of that evening.

Credit : Flyer, Missing Call FBI, ca. 1964. Freedom Summer Text & Photo Archive, Miami University, Western College Memorial Archives, Oxford, Ohio

Concerned but still determined, the staff and volunteers of the Freedom Summer Project continued on with their mission to register voters and foster a freedom movement, although the mood at the training sessions in Oxford had shifted.

A few days after their disappearance, the blue station wagon was found burned off the side of the road. The case of three missing men began to draw in national attention, in part because Schwerner and Goodman were both white Northerners. In 1964, Mississippi was the only state without a central FBI office, but on June 22, agents from the New Orleans office arrived to begin a kidnapping investigation. More agents would come to Mississippi over the next several days, ultimately totaling more than 200. Their names became national news as the search for them began.

Throughout July, investigators combed the woods, fields, swamps, and rivers of Mississippi, ultimately finding the remains of eight other Black men. After six weeks of searching, the FBI uncovered the bodies of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner on August 4, 1964. Their murders were tied to the Ku Klux Klan.

This devastating news swept the nation and to this day, their murders are often remembered as an extremely somber, yet pivotal point in the history of the Freedom Summer Project.

In a letter titled "A Reflection on June, 1964 and Racism, Then and Now" one volunteer wrote:

"I remember vividly what it was like for the staff and volunteers of the Mississippi Summer Project on the Western College Campus in the days following our learning that Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman had disappeared in rural Mississippi...

We cried a lot. We hugged. We spoke in groups of two and three and four late into the night. Together we joined hands, swayed back and forth, and sang freedom songs until we were hoarse. Some of the volunteers left, to go home. Several more were removed by terrified parents. Almost all stayed, and then went on to their assignments, mostly in Mississippi, but also in Georgia, Louisiana and Alabama.

Mostly, however, we went on with the training. How to do art enrichment with children who had never been to a school with art supplies or teachers. How to teach basic literacy to children whose segregated schools had failed them and to adults who had had little schooling of any sort. How to cope with voter registrars at county courthouses when they sought to disqualify Negro applicants for registration. Workshops on the philosophy and tactics of non-violent protest; how to protect oneself when assaulted; how to prepare oneself to respond nonviolently to violent provocation and attack; why we were committed to nonviolence as a technique for social change, and why many in SNCC were committed to nonviolence as a way of life."

Credit : The Mark Levy Collection, The Civil Rights Archives of the Queens College. Freedom Summer Text & Photo Archive, Queens College Special Collections and Archives; Western College.

The national attention the Freedom Summer gained for the Civil Rights Movement— largely due to the murders of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner— helped convince President Johnson and congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin, as well as passing the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Some call Freedom Summer 1964 one of the most historic and ambitious efforts in the Civil Rights Movement, bringing national attention to the shocking violence and injustice in Mississippi. Although the events led to positive political action, it is imperative to remember the people behind the Freedom Summer Project; the community of different volunteers that came together in these times of education, times of danger, times of mourning, and times of hope.

The Freedom Summer Memorial

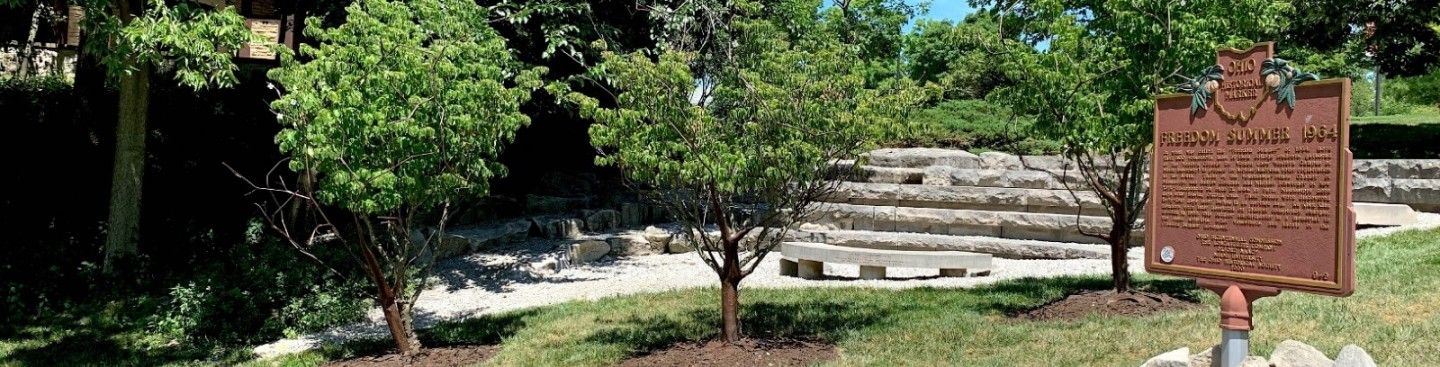

In the area where so many brave people trained in the fight against violence, mourned the loss of fellow volunteers, and sought to make a difference, it became important to the Oxford community to construct a memorial commemorating the people and the place that impacted Freedom Summer.

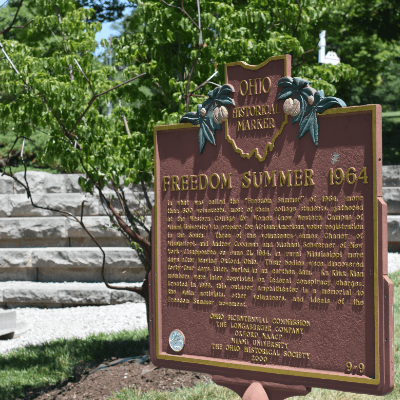

Dedicated in 2000, a stone monument was built on the grassy hills of Miami's Western Campus, where the Western College for Women once stood. The memorial can be seen around the side of Kumler Chapel, alongside an Ohio Historical Marker, and three trees that were planted to honor the lives of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman.

At the memorial’s groundbreaking, Miami and NAACP officials said, "It’s important for young people to know the sacrifices of those who fought for a fairer, more just society."

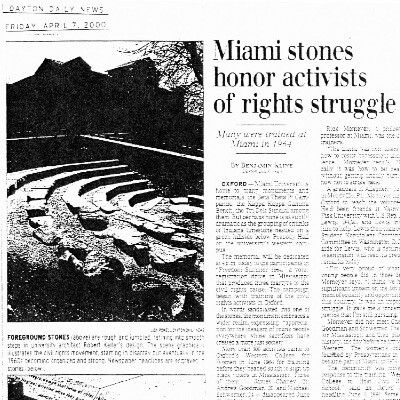

Credit : The Dayton Daily News, April 7, 2000. Freedom Summer Text & Photo Archive, Miami University, Western College Memorial Archives, Oxford, Ohio.

Engraved in the back of each stone panel are headlines and bits of information, representing a chronology of events as depicted by newspapers around the country in 1964.

The Freedom Summer Memorial is meant to be immersive.

The memorial in its entirety can be greatly described as a solemn experience in layers of legacy. As you step down through each stone bench, there is a layer of education about the impact of Freedom Summer; a layer of honor as you remember of the sacrifices of great activists; and the overarching layer of being consumed by the true representation of hope.

"Recognizing that a part of our campus ... played such a monumental role in the Civil Rights Movement is something that's really important to not only history but Miami's history in particular. We recognize that that's something that our students should not go through a Miami University experience without knowing; that this history is actually here and took place on the same grounds that we walk around every day," Miami Student and 2019 Student Body President, Jaylen Perkins, said in an article published in 2019.

Both the Oxford community and Miami University continue to shine more light on the historical events and workers of Freedom Summer to this day.

The Changemakers of Oxford Mural

The most recent tribute to Freedom Summer and Oxford's history is highlighted in a bright, public mural that can be spotted across from the Oxford Community Arts Center.

In September of 2019, Oxford Resident and Girl Scout Ella Cope, presented the Changemakers of Oxford Mural to her community— a project that Ella had been working on for over a year. As a Girl Scout since she was about 10 years old, Ella Cope had to complete one last major project in order to receive the Girl Scout Gold Award which is the highest honor in Girl Scouts.

The only major criteria for this project is that it has to leave a positive impact on the individual's community. With a lot of work, planning, research, and paint later... Ella created a mural that does just that, and will continue to leave a positive mark on Oxford for years to come.

The mural highlights important events, activists and symbols of civil rights history in Oxford— including Freedom Summer, John Jones, and the Underground Railroad.

When Ella first began her project, she knew she wanted to create a piece of public art for Oxford. As Ella put a lot of thought into her final Girl Scout project, she says she remembered a trip she took in the third grade to the Freedom Summer Memorial.

"It's a part of Oxford's history that's not as well known. I decided I wanted to take that aspect of lesser known, yet important history and bring it into the spotlight," Ella explains. "You shouldn't have to be pursuing an academic project to be aware of your local history."

When looking closely at the mural, you can see just how many different aspects of civil rights history is represented. Everything from the map in the background, to the railroad tracks, to the blue station wagon holds great significance.

"Once you know the significance in the mural, the station wagon is a great visual metaphor. It's the idea of forward motion," says Ella. "There is this constant forward motion and as long as the car is pointed in the right direction, and passengers keep getting in... we know we're doing the right thing."

To Visit & Learn More

Visit The Freedom Summer Memorial — Behind Kumler Chapel at Miami University, 650 Western College Dr. | Oxford, OH 45056

Visit The Changemakers of Oxford Mural — Across from the Oxford Community Art Center, 10 S College Ave. | Oxford, OH 45056

To Learn More, Visit the Lane Libraries — 441 S. Locust St. | Oxford, OH 45056 | www.lanepl.org

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jacqueline Johnson at the Miami University as well as Valerie Elliott at the Smith Library of Regional History for their time, information, and assistance.